Throughout the evolution of the Robyn

Hode ballads and folk tales, artists

have tried to visually depict Robyn

and his outlaws such as Little John, Will Scarlet,

Sir Richard atte Lee, Guy of

Gisborne, the nameless sheriff of Nottingham,

Roger de Doncastre, the Prioress of

Kirkely, and

Maid Marian. Each time the heroes and

villains appear dressed in the fashion

of the time. Most people are

familiar with the green felt peaked hat with the feather, the short coat and

green leggings or even the filmic heroes tights. However, if we examine

illustrations from various publications in different fashion eras we find

that this 20th and 21st century appearance is not altogether apparent in earlier styles. Below

are examples of the types of clothing that have been used over the years.

Throughout the evolution of the Robyn

Hode ballads and folk tales, artists

have tried to visually depict Robyn

and his outlaws such as Little John, Will Scarlet,

Sir Richard atte Lee, Guy of

Gisborne, the nameless sheriff of Nottingham,

Roger de Doncastre, the Prioress of

Kirkely, and

Maid Marian. Each time the heroes and

villains appear dressed in the fashion

of the time. Most people are

familiar with the green felt peaked hat with the feather, the short coat and

green leggings or even the filmic heroes tights. However, if we examine

illustrations from various publications in different fashion eras we find

that this 20th and 21st century appearance is not altogether apparent in earlier styles. Below

are examples of the types of clothing that have been used over the years.

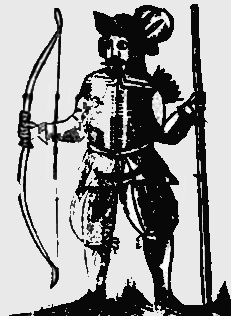

The typological image at left depicts a re-curved bow, not a longbow.

He carries a hunting horn at the waist and a sheathed sword, a quiver of

arrows is slung across his back. [From a 1970's lace

tapestry made in Nottingham]

The 'yeoman' in the 1491 edition of the Geoffrey Chaucer's Canterbury Tales:

This woodcut by Richard Pynson was the first attempt to provide a visual image of the ballad hero when it was re-used in the ballad, A Lytell Gest of Robyn Hode [National Library of Scotland]. Robyn wears a cap or hat tied on with a band or ribbon. There is no feather in his cap. He has a full coat with long wide sleeves and what appear to be boots with spurs. He carries the traditional longbow and arrows, the arrows were probably tucked into his belt. [Quivers are not evident at this time] This image was probably re-used because the Gest refers to Robyn as a 'yeoman', essentially a gentleman farmer.

From the frontispiece of Wynken de Worde's publication of A Lytell Geste of Robyn Hode:

The

headwear indicates a type of beret, Robyn wears what appear to be tight trews,

a kirtle* with long sleeves fastened at the waist with a rope or belt which

holds an enormous scabbard. He carries a large sword to match, referred to as a

'bright bronde' in the Gest. His hair is almost shoulder length and

he is clean shaven. In the full image, the prioress also appears and probably

Roger de Doncastre. Scrolled labels are above each individuals head but

either the names have been removed or obliterated by time. In the

illustration no bow

or arrows are evident. * Kirtle O.E. cyrtel,

probably from cyrtan, a short coat, probably the origin of the words

'skirt', 'curtain'.

The

headwear indicates a type of beret, Robyn wears what appear to be tight trews,

a kirtle* with long sleeves fastened at the waist with a rope or belt which

holds an enormous scabbard. He carries a large sword to match, referred to as a

'bright bronde' in the Gest. His hair is almost shoulder length and

he is clean shaven. In the full image, the prioress also appears and probably

Roger de Doncastre. Scrolled labels are above each individuals head but

either the names have been removed or obliterated by time. In the

illustration no bow

or arrows are evident. * Kirtle O.E. cyrtel,

probably from cyrtan, a short coat, probably the origin of the words

'skirt', 'curtain'.

1640 About Robin Hood and the Butcher:

Again a kirtle and some form of hat are evident, perhaps with trews tucked into long stockings or boots.

An image borrowed from The Tale of Adam Bell 1640:

From

a broadside publication,1687 Robin Hood and Queen Katherine, the image

was borrowed from The Tale of Adam Bell, both published by William

Thackeray.

Here Adam/Robyn wears a doublet and a flamboyant post-Elizabethan style hat and feather. The pantaloons are of a similar time, a shield, sword and knee high boots with spurs complete the outfit. Here he sports what appears to be a full beard. He carries no bow or arrows although one of his companions does.

About 1660 from a broadside, Robin Hood and the Shepherd:

Again a flamboyant hat but no feather, a shirt with long sleeves and cuffs, pantaloons braided at the bottom, long stockings or knee-high boots with spurs. Robyn appears to be bearded. He carries arrows in his belt. [Bodleian Library, Oxford]

1700 From the title page of Robin Hood, A History:

A

flamboyant hat and large feather, tunic fastened at the front and tied at

the waist, the sword is gone replaced by a staff with the ubiquitous

longbow. He wears pantaloons tied below the knee with knee high stockings.

He carries a long bow and arrows perhaps in a quiver on his back.

A

flamboyant hat and large feather, tunic fastened at the front and tied at

the waist, the sword is gone replaced by a staff with the ubiquitous

longbow. He wears pantaloons tied below the knee with knee high stockings.

He carries a long bow and arrows perhaps in a quiver on his back.

1791 from a broadside, Robin Hood and Little John:

Clothing

of the style of the time, tight trousers, cocked hat and a buttoned waistcoat.

~1795 an edition of Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne from an engraving by Thomas Berwick in Ritson's Robin Hood:

Robyn wears a shawl or hood, a tunic and tight trews. Here he fights Guy

of Gisborne with a sword.

The same edition as above showing an engraving again by Thomas Berwick from Ritson's Robin Hood:

This time the artist has Robyn wearing a broad-brimmed hat with a large feather, long-sleeved shirt, knickerbockers and short trousers tied below the knee with knee high stockings. His hair is long and he is clean-shaven. He wears on his back what appears to be a quiver of arrows.

1850 from an edition of Pierce Egan's Robin Hood and Little John:

A

dark haired, fully bearded Robyn, wearing a collared tunic which was buckle belted at the

waist and a buckle sash belt, trews and strapped, possibly buckled shoes

are de rigueur.

1850 Pierce Egan's title page to Robin Hood and Little John:

Here the image of Robyn is becoming more like the familiar 20th century versions. A much less flamboyant hat, the feather, which seems to have made an appearance in the 1600's is still there. A collared kirtle or tunic and a sash belt, shoes, perhaps buckled. He sports a very debonair moustache.

1883 Howard Pyle's The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood:

Pyle retains the feather atop a hat whilst he incorporates the medieval long-toed leather shoe. Chain mail makes an appearance under what appears to be a knight's surcoat, suggesting a knightly background. However, there is an absence of spurs. He carries arrows in a quiver and a full beard. Importantly he looks jolly, a reflection of the impishness of the Gest. The 1800's were a time when the Robyn Hode stories were not only heroic but were given market-driven romantic attributes.

1922 The filmic Robin Hood and Maid Marian with Douglas Fairbanks as Robyn:

'A

silent film' from the 'Roaring Twenties' with strong elements of romance. Marian who does not appear in

the early ballads becomes that significant other. Tights become the

signature with cloaks and expensive tunics. Robyn has a goatee and

moustache.

'A

silent film' from the 'Roaring Twenties' with strong elements of romance. Marian who does not appear in

the early ballads becomes that significant other. Tights become the

signature with cloaks and expensive tunics. Robyn has a goatee and

moustache.

1938 The archetypal Robin Hood film with Errol Flynn.

Perhaps the most loved of the Robin

Hood films with the impish character, agility and energy of Errol Flynn matching

that of the character in the original ballad of the Gest. This Technicolor®

film

has influenced most of the 20th century if not the 21st into believing

that Robyn was a thieving rascal clothed in green who lived in the forests

of medieval England whilst seeking freedoms and justice for the common

man. The peaked cap and feather became part of his popular image in the

modern psyche. The quiver became a permanent feature, although this was

not in general use until Tudor times. Despite being Tasmanian born, the

accent of Errrol as Robyn was 'cultured English', the domain of the English

'public school' often considered to be elitist by the truly provincial

English. However, Robyn was not a member of the ruling

descendant Norman class, for to be so would mean he would have spoken

Norman-French. If he was truly provincial English, a yeoman or freeman,

neither serf nor noble, as I have evidence that he was, then he would have

had an English regional accent. One other major error in the film is the

pre-occupation of 'Saxons' versus 'Normans'. This was based upon Sir Walter

Scott's interpretation [Ivanhoe, 1819], a piece of fiction i.e. a totally spurious and

speculative falsehood. Quite clearly, Normans and Saxons are never mentioned in the

early ballads. By the reign of Richard I the English and the

Normans were well assimilated into a feudal society, those tied to their

lord and his manor were loyal to him in order to retain their own

security. Like Scott's attempt to prove that Scottish tartans had an

ancient origin, this fictitious profligacy by Scott has fooled anyone

hoping to prove the existence of an inspirational Saxon character for the

ballad hero.

The film lacks any genuine English scenery, being mostly filmed in the back-blocks of Burbank Studios and the 2200 acre Bidwell Park, Chico, California, 100 miles north of Sacramento and 475 miles N.W. of Los Angeles. Here large oaks and sycamore trees grow in an otherwise dry environment, amply assisted for the film, with suitable rock and tree stumps imported for the effect. Foregrounds were real whilst backdrops, such as castles, were matte painted on glass. Olivia de Havilland played Marian. This folk name is not mentioned in the early English ballads at all, nor does the balladic Robyn have any romantic involvement, these are later pieces cobbled onto the oral histories, plays and ballads beginning in the1600's and reaching their zenith in printed form during the 1800's. One interesting item in the film is the fact that Olivia de Havilland's horse later became Roy Roger's 'Trigger'.1 The 'splitting of the arrow' too was shown incorrectly. It is correctly called the 'splitting of the wand' whereby the wand is stuck vertically into the ground. Trying to spilt an arrow 'end on' is nigh impossible as was demonstrated in a popular television programme, Mythbusters, yet even they were trying to recreate the filmic version of the event. In the 1938 film a mechanical device was used to aid in this visual effect. In my informed opinion the Hollywood film industry, primarily a machine for producing passive entertainment, has added to the storm of misinformation regarding the origins of the inspirational character, and this continues in the more recent spate of films. The English need to seriously retake control of this runaway locomotive.

1952 A carved relief at Castle Green, Nottingham:

The filmic versions were well underway by now, such as Disney's 1952

version with Richard Todd in the lead role. These events helped to influence the artist's rendering of what he thought Robyn looked like. The seemingly ubiquitous

feather makes an appearance, staffs or staves are in order whilst Robyn

and Little John wear close fitting leather caps or hoods. Robyn wears a

short-sleeved shirt, a waistcoat and carries a sword in a scabbard at the

waist. Little John has a quiver of arrows. Again there is deference to the

long-toed medieval leather shoe. By 1952 researchers were beginning to try

to match the ballad exploits to an historical character which produced

conflicting and very contradictory results.

1955-1958, Richard Greene of the tele-visual Robin Hood:

Probably

the closest the film version came to the 'Lytell Geste of Robyn Hode'

whereby Sir Richard atte Lee appears. Here

Robyn is presented as a dispossessed knight who takes to the Greenwood. In

the first episode, The Coming Of Robin Hood, Robyn returns to England

after crusading in the Holy Land. This of course is balderdash. This theme was incorporated into the 1991

'Prince of Thieves' film. By such 'borrowings' we can see how the stories

have evolved so very far from the original early ballads,

particularly the Gest, where except for the Richard Greene

television series, Sir Richard atte Lee has been convincingly eradicated

from all scripts. Robyn wears chain mail and knightly attire

before discarding this garb to dress as the outlaw with green cap and feather. Although there are some English landscape scenes, much of it was filmed at

Elstree studios using mobile stage sets. Again the film was set in the reign of

King Richard I using Prince John (Donald Pleasence) as his nemesis while

Patricia Driscoll played Marian.

Probably

the closest the film version came to the 'Lytell Geste of Robyn Hode'

whereby Sir Richard atte Lee appears. Here

Robyn is presented as a dispossessed knight who takes to the Greenwood. In

the first episode, The Coming Of Robin Hood, Robyn returns to England

after crusading in the Holy Land. This of course is balderdash. This theme was incorporated into the 1991

'Prince of Thieves' film. By such 'borrowings' we can see how the stories

have evolved so very far from the original early ballads,

particularly the Gest, where except for the Richard Greene

television series, Sir Richard atte Lee has been convincingly eradicated

from all scripts. Robyn wears chain mail and knightly attire

before discarding this garb to dress as the outlaw with green cap and feather. Although there are some English landscape scenes, much of it was filmed at

Elstree studios using mobile stage sets. Again the film was set in the reign of

King Richard I using Prince John (Donald Pleasence) as his nemesis while

Patricia Driscoll played Marian.

Many of the television scenes were filmed at Sir Lew Grade's studios in Elstree where scenes were erected on wagons that could be towed to different locations. Some 'real' scenes may have been filmed in nearby Boreham Wood.

1991 The Kevin Costner Prince of Thieves film:

This

film followed on from the Flynn characterisation but the American accent

grated on the English ear. However, its utilisation of some real English scenery

was a positive attribute, such as the Dover Cliffs, Aysgarth Falls in

Wensleydale and even 'Sycamore Gap' on Hadrian's Wall. Again Robyn was an outlaw or

thief residing in the forests, this time clad in studded leather.

This

film followed on from the Flynn characterisation but the American accent

grated on the English ear. However, its utilisation of some real English scenery

was a positive attribute, such as the Dover Cliffs, Aysgarth Falls in

Wensleydale and even 'Sycamore Gap' on Hadrian's Wall. Again Robyn was an outlaw or

thief residing in the forests, this time clad in studded leather.

2010 The Russell Crowe film:

Returning from the Crusades with King Richard, Robyn helps in the siege of what is ostensibly Chaluz Castle. However, a historical error is made early in the film when the person who shoots the arrow at King Richard is shown as a mature man even though in history he is recorded as a young boy. As Russell has said, this is 'our Robin Hood'.

The mock castle from the 2010 film |

Chaluz Castle today |

A critique of the film:

As an impersonator, 'Robert Longstride' an archer in King Richard's retinue, takes the name and title of Sir Robert of Loxley from the dead knight of this

name, the dominus of Loxley. Crowe mumbles too much throughout the film and is not convincingly charismatic enough

to command respect in order to weld men together under a common cause.

He subsumes, deliberately or otherwise, his character to that of Marian [Blanchett].

In a different twist to the fictitious story, Marian appears as a strong-willed and independent dame managing her manor of Loxley.

This is probably much closer to the truth for a medieval dame, who had to

replace her husband while he was away on business, visiting his other

manors or at war. The characters of the 'merry men' do not appear convincing either and lack any real

spirit of camaraderie. 'merry' in its original form did not mean 'happy and/or drunk', this is

an erroneous and modern interpretation of the term. Instead it means being

sworn to an (blood?) oath towards a common cause, in the case of the Gest,

to be rid of the 'Sheriff of Nottingham'.

Robyn is made out to be a leader of the barons for Magna Carta with 'liberty' and 'freedom' being catch-cries, yet these concepts in history are essentially those of the barons seeking more land and control for themselves, certainly not a munificent gesture towards the English commoner. The Peasants Revolt in 1381 led to some freedoms from their feudal lordships but not because the people were given freedom, its achievement was hastened because of the huge depletion in the work force. The peasants, as with all levels of society had, from 1349, been reduced by the Pestilence and could now offer their labour on the market to the employer who would pay the highest price. Freedom was never given, it always had to be fought for and sometimes the fortuity of nature played a helping hand. The commoner would have to wait for another 800 years to begin to enjoy the benefits of one-person-one vote and the rewards which flowed from this. If this had not happened over a period of time we would all now probably be shackled and marginalised by self interested religious zealots, cult figures and military madmen. Burma and Thailand look and weep, you need your own Robin Hoods, let's hope it doesn't take you 800 years to achieve democracy.

Even stranger in the 2010 film, Robyn teams up with King John to repulse a French invasion.

In popular modern history King John has been vilified as a cruel tyrant, yet he was an able administrator and

probably no more

despotic than any other medieval English king. Henry II, Henry III and Richard II could

be seen as

equally tyrannical. A primary reason that John is held in such low

regard evolved from the fact that he lost many English baronial lands in France.

In particular, it was the barons who hated him and it seems that this continual claim by English

barons to their lost lands in France served to create rifts between the succeeding kings and their barons. This

explains why the French noted that the king's of England had a grand tradition

of troublesome or rebellious barons. John's parlous situation was a result of the

treasury being grossly depleted by King Richard I in his wasteful crusading. It should be King Richard who is held up

equally to scorn as he sold the northern English counties to Scotland for 100,000 pounds, reduced England's treasury to an all-time low and left a degenerate political legacy for John and subsequent kings to manage.

Is it any wonder that the commoners hero, 'Robin Hood' has once again been selected, falsely, to have lived during King John's reign.

Edward I did exactly the same in his conquests of Wales but more

particularly with his campaigning in Scotland, leaving his ineffectual son to pick up the

pieces of a devastated treasury. Something similar has recently happened in British politics. The present incumbents are likely to go down in history as equally harsh masters as they begin

their cutting of essential public services, a so-called period of

austerity. Yes, history is about to be repeated, as sure as day follows

night, 'bust' follows boom.

The arrows of austerity still raining down on us

Proclamations nailed to a tree are an error, particularly penned in modern English. Virtually nobody except the clerics could read and then it was exclusively in Latin. Proclamations issued by the sheriff of each county would be read aloud on market days in the county market place and thereafter news would have travelled orally. The cliffs of Pembrokeshire, South Wales are no substitute for the chalk cliffs of Dover, while the culminating battle seems to be a combination of the battle of Hastings and the Normandy D-Day landings. On the plus side, scenes are immersed in a detailed and realistic visual treat of 'medieval' ambience whilst many castles and backdrops are cleverly incorporated care of C.G.I. Why the film was given the title 'Robin Hood' is a little difficult to understand, apart from the expensive and gratuitous battle scenes, perhaps it should have been titled something like 'Medieval Outlaws' and been made into a tele-visiual extravaganza. The film hyperbole claimed that we have all been 'waiting decades' for this film, but if this was a 'prequel', we can only hope that the sequel has more than 48 hours spent on the script and Robyn gets a bit of humour back into his dialogue. Perhaps a few Seamus Bondian quips wouldn't go astray, after all, if you are going to present fiction you may as well make it entertaining.

So what did the inspiration for the ballad character really look like? Suffice it to say, he seems to have led a double life, sometimes dressed as a knight and at other times perhaps as we have come to imagine him. Perhaps the Richard Greene version of the hero was the closest of the many attempts to portray the real person behind the Gest, but it has to be added that he was never involved in the crusades, that is most definitely another piece of embellished fiction.

Sources:

1. Holt, J.C. Robin Hood, Thames and Hudson, 1982.

2. Harris, P. Valentine. The Truth About Robin Hood, 1952.

3. Dobson, R. B. & Taylor, J. Rymes of Robyn Hood Hood. Heinemann, 1976.

4. Behlmer, Rudy. Behind the Scenes. 1989.

|

| Oh yes, those cliffs of Pembrokeshire! |

We all hear statements like "Was Robin Hood real?" or titles to books and web sites like, "The facts and myths of Robin Hood'" but none of them ever give a definitive answer. Is this because they have not found proof positive? Are they having some sort of romantic wishful exercise to convince themselves there is something innately good about the human spirit in this sometimes heartless world?

Well here are a few actual historical facts rather than romantic notions. Here is what the 'Robin Hood' ballads were NOT:

They were not set in the reigns of King Richard I or King John.

The Normans were no longer Normans by Robin's time, they considered themselves Anglo-Norman or even English.

He was never in the Crusades nor did he fall upon the shores of the White Cliffs like a desperate modern day refugee.

He was never recorded on Hadrian's Wall at the so-called Sycamore Gap, Hardraw Force, Aysgarth Falls etc. etc.

The 'merry men' did not usually reside in the woods, they preferred the 'comfort' of manor houses and castles.

There was no forest of Barnsdale. Forests had strict laws with bailiffs and foresters to control them.

'Loxley' was never a castle, but a wooden manor house until it was fortified.

The 'sheriff of Nottingham' was never a sheriff.

Robin's father was never dispossessed although Robin was and his son had to pick up the pieces.

Robin did not have a Southern English or American (quasi SW English) accent.

'Little John' was not called John Little.

Robin's marriage was an arranged one, the church that he and his bride were married in can still be visited today.

'Marian's' place of burial is known and her effigy can be visited.

Robin was not poor he was 'bank-rolled'.

There is no evidence that he 'took from the rich and gave to the poor', this is a later unsubstantiated accretion.

Interested? Then work harder

and you will find that all the sceptics, post medieval chroniclers and

professional historians are all very misled by their own deep-seated

doubts!

![]() Home

Home

© Copyright Tim Midgley 2005, Revised 13th November 2024.